I’ve found Twitter Blue’s implosion to be massively fascinating for a multitude of reason. It goes against all common sense, and even Musk’s own tried and tested marketing strategies. Everything that went wrong was completely predictable and many, including myself, wrote about it ahead of time. The biggest question is why it went ahead, but only one person can answer though, so instead I’ll analyze the many hows & whys of its failure.

History of the Blue Check: verification, vanity, or something else?

Twitter’s verification icon, commonly referred to as the ‘bluecheck’, has always been a bit confusing. The initial purpose was illustrating that notable accounts are who they say they are. Twitter’s intent was somewhat distorted by their decision to revoke bluechecks from misbehaving accounts. These people did unbecome notable, or unbecome themselves, which led rise to the idea that the checkmark was more than just verification. It was a pseudo-endorsement by Twitter.

Things got extremely complicated in 2017, when Twitter decided to lower the requirements for verification and allow users to apply. They put a focus on verifying journalists, a good idea in theory, but the implementation was wrong. Twitter essentially dropped the notability requirement to the point where one could obtain verification by simply writing a couple of blog articles.

Several prominent neo-nazis were able to obtain verification through the application system, which caused a major backlash against Twitter. Given Twitter’s previous use of the verification system as a pseudo-endorsement, users were rightfully confused. Was Twitter simply saying these people are notable enough, or were they now endorsing white supremacy? Either way, it wasn’t a good look.

Now, the answer to whether the blue check is verification or an endorsement? It’s both and neither. Twitter has inadvertently created a sort of bluecheck superposition. The bluecheck means both everything and nothing, until it is observed. It’s certifiably true that intended or not, the bluecheck boosts the recipient’s visibility. It both provides a visual distinction, drawing the user’s eyes toward the tweet, on top of adding an air of legitimacy or trustworthiness to the poster’s account. Like anything exclusive, it’s also become seen as a symbol of status or vanity, mostly by those not in possession.

Cashing the blue check

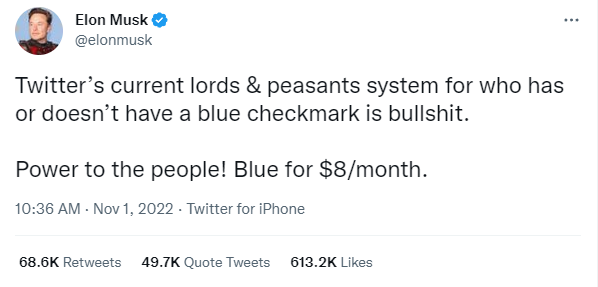

Early on it was made clear that the blue checkmark would not include any identity verification, something myself and others had already raised the alarm about. It was clear the feature would be used for impersonation, but that isn’t the primary reason it failed. There’s a couple of different ways Musk could have ‘sold’ Twitter Blue, but he seemed to fixate solely on the idea of blue checkmarks as a status symbol. It actually wasn’t even clear what other features Twitter Blue would have.

It’s evident that Musk considered verification to be a symbol of status, yet tried to mix in populism.

It’s evident that Musk considered verification to be a symbol of status, yet tried to mix in populism.

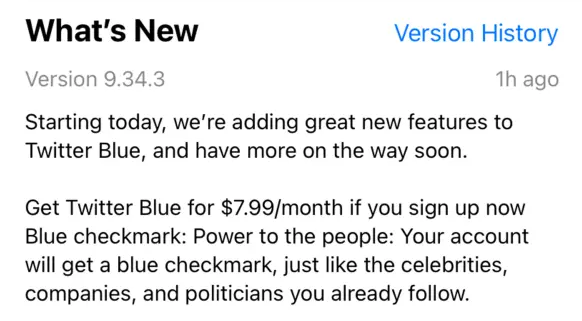

Twitter’s feature description leans in to the bluecheck-as-a-status narrative.

Twitter’s feature description leans in to the bluecheck-as-a-status narrative.

Whilst it would have been possible to sell the blue checkmark as a status symbol, Musk seemed to misunderstand the psychology behind the idea. Buying status isn’t a new concept, it can be seen everywhere from designer clothes to exclusive sports club memberships. The major difference, of course, being requirements. In order for something to be a status symbol, there must be some kind of prohibitive social or economic barrier. After all, if everyone can have something, then how can it possibly be a sign of status?

Now, I want to make it clear that I think trying to turn the bluecheck into a status symbol was a horrible idea, but it was technically possible. The implementation, however, missed the mark by a several hundred nautical miles for a multitude of reasons.

The psychology of socioeconomic status

I personally got something I refer to as the “sympathy checkmark”, which is where you’re not considered notable enough to qualify for traditional verification, but get it anyway due to issues such impersonation by scammers. I’ve never really seen it as a status symbol, but I can understand why others might. The two most common ways to get a bluecheck are to either by being a celebrity, or being a notable leader in your field, both of which implicitly carry a certain level of status.

Most economic base status symbols fit into one of two categories:

- Things that the average person could afford, but would have to work towards.

- Things that are easily affordable to the extremely wealthy, but completely unobtainable for the masses.

The designer brand model

We see group 1 targeted by a lot of designer brands. Celebrities hawk medium-expensive apparel, attaching their status to it in the process. The semi-prohibitive price point combined with the celebrity’s own status, gives an illusion of higher-than-actual socioeconomic status to the buyer. The system, however, only works if buyers feel like the effort they put in to affording the item distinguishes them from others (i.e. the cost can be low, but must be relatively high for the target audience).

Twitter may have been able to exploit this with Blue. By combining the status radiated by existing bluecheck with a relatively high price point, they could have created their own designer brand. The problem, was the monthly subscription. For something that costs about the same as a netflix account, Blue wasn’t going to give any reasonable buyer the impression that they had achieved anything. In fact, it was so affordable that the price essentially reversed the illusion of the bluecheck being a status symbol.

A more successful approach would have involved high upfront cost, followed by a low maintenance fee. The high upfront cost would replicate the medium-expensive price point of low-end designer brands, with the maintenance fee being an optional extra to exploit sunk-cost fallacy.

The golf club model

Group 2 would have been much trickier to work with, but may still have work. Instead of targeting normal users, the goal would be to have fewer users paying more. This is what I call the luxury golf club model. Instead of marketing to the masses, Twitter would turn the bluecheck into an exclusive club by setting a highly prohibitive price point. Something that’d be worth it to celebrities and brands, but not so low that the average user could afford.

Allegedly, there were Twitter employees selling bluechecks under the table for tens of thousands of dollars. At that supposed sale prices, this would put a single buyer being worth as much as 1000 - 5000 Twitter Blue users. Such a high price could have allowed Twitter to heavily monetize the bluecheck, without entering a tailspin of trying to sell it as a status symbol whilst simultaneously dismantling its allure as a status symbols.

Failing at every possible level

I want to make it clear that I’m against monetization of bluechecks. I think the idea of trying to sell socioeconomic status is sleazy at best, but the part that fascinates me is how Musk somehow managed to fail at such a well documented grift.

Many people see Twitter Blue as a failure due to the rampant impersonation, and I don’t disagree that the impersonation issue was a huge, albeit absolutely hilarious, failure. But even without sexual Joe Biden tweets and self-destructing brands, it’d still have been a monumental failure.

The low price-point created a death spin by making the checkmark accessible to everyone, instantly vaporizing the illusion of status Musk had attempted to sell it on. As a result of the extremely low price point, only two kinds of people were signing up.

- People who just wanted Twitter Blue’s other feature (which would have made far more sense to sell separately).

- People insecure enough to willingly seek out the validation of paying $8/month for a 400 pixel logo.

The problem with people in group 2 is the high overlap between insecurity and toxicity. On top of having already destroyed any illusion of status the bluecheck may have had, the kinds of people now touting it were those with whom neither original bluechecks nor group 1 wanted to associate. Essentially, Twitter’s attempt to cash in on what they thought was a status symbol created the exact opposite condition. The minority of people who bought Twitter Blue for status deterred all other potential customers.

The whole situation could have been easily avoided by not trying to market the bluecheck as a status symbol. But even with the decision to market it as such, it could have been given a much better prospect by separating Twitter Blue, Vanity bluechecks, and original bluechecks. For reasons unknown, Musk decided to put all his eggs into one basket, load the basket onto a sinking ship, then set the ship on fire. His actions have irreversibly shattered the illusion of the bluecheck as both a verification symbol and a status symbol, ensuring it is no longer viable for either.

Conclusion

I don’t buy into conspiracies, but it’s really, really, difficult to believe that this was a mishap consisting of many overlapping failures, and not a deliberate attempt at destruction. After all, Musk has successfully, pulled off feeding into people’s desire for the appearance of status before.

Tesla’s Roadster launched as a luxury vehicle capable of outperforming a Porsche 911. It was by all means a luxury car, with a luxury price of $120,000. Over time, Tesla launched more and more models, slightly lowering the price each time. This maintained the impression of luxury, whilst capturing more and more buyers. Even the $35,000 Model 3 provides many with the feeling of extravagance typically only provided by high-end vehicles. I’m sure Teslas could continue to maintain their allure at even lower price points.

So the question is, why didn’t Musk do the same with Twitter Blue? Why did he make the decision to start at the lowest price possible and then work his way up? There are arguments for a Netflix style model. Blue could have started with a low introductory price, then bumped up the cost once they’re sure people are willing to pay to keep it. But as to why Musk decided to combine two opposing marketing models, and have them cancel each-other out; we’ll probably never know.